Ukraine: Europe's last Gas Frontier?

In the past 10 years, "Ukraine" and "gas" have together been associated with the country's strife with its eastern neighbour, and by extension, with Europe's security of supply concerns. Given this, it is easy to overlook Ukraine's importance as a gas market in its own right. At 42.6 billion cubic meters (BCM) in 2014, the country's gas market ranks a close 4th in Europe, after Germany's (86.2), UK's (78.7) and Italy's (68.7). The market size is likely to continue to shrink for either good reasons - improved energy efficiency, better metering of flows - or for bad ones - economic recession - but at the same time, it is bound to stimulate greater interest among Europe's gas traders because it is the last gas frontier that is truly open to them to conquer. Indeed, Ukraine is unique in that its incumbent gas system operator Naftogaz of Ukraine, welcomes newcomers onto its market. At a conference held on 23rd April with European gas traders,[1] Naftogaz's CEO Andriy Kobolev called for greater competition on the domestic market and diversity of supply.

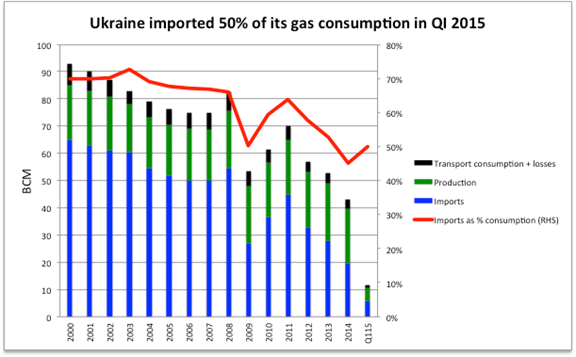

Source: NGBI based on data from the Ministry of Energy and Coal Industry (2000-2014), Energobusiness (Q1 2015)

Ever since Ukraine gained its independence, the economy has been handicapped by its high degree of energy-intensity and by the price it pays for gas, both for industry and for residential consumers. While Ukraine has paid somewhat higher prices for its imports of Russian gas than its geographical position would warrant, the crux of the problem has been that the price residential consumers have been paying (when they pay it) has been far lower than even the import price. An unreal price of about $100 per thousand cubic meters (kCM) on the 11.3 BCM the residential sector consumes[2] has been a drag on the country's state-owned gas company Naftogaz, and therefore on the country's debt. Likewise, the need to reform the complex and corruption-prone multiple gas pricing scheme[3] is almost as old as Ukraine itself, but successive governments have postponed reform, fearing a popular backlash.

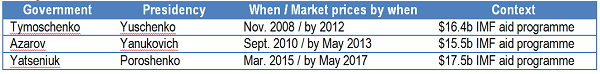

The graph below shows successive governments' commitments to raise the domestic price of gas to "market levels". The dotted line indicates the intended rise in tariff, and the yellow line, the actual weighted average tariff for various categories of residential consumers.

Source: Kobolev, NaftoGaz, Kiev gas conference 23/4/15

With Ukraine's economy decimated by the war and the occupation of Crimea and the Southeast, the government is more than ever tributary to the West's financial assistance, and in particular, the $40b bailout package it agreed with the IMF in February 2015. The government has taken steps to show its commitment to reforms. In the gas sector, this has taken the form of the Law on the Gas Market[4]which, in its convoluted 70 plus page form, does seem to address the key issues. It calls for Ukraine's gas transportation system (GTS) to be operated in a way consistent with Europe's 3rd Energy Package. This entails removing the subsidies on domestic gas consumers, giving third parties regulated access to the GTS, moving towards an entry/exit tariff structure for transportation and storage, and empowering the market regulator to vet traders on the market. With these encouraging signs, Europe's gas traders are mobilising to supply more gas to Ukraine's Western borders, and perhaps soon, to Ukraine's large consumers. Interestingly, the prospect of importing gas into Ukraine from the West -backhauling as it is called- was first raised before the Maidan revolution, when then-president Yanukovich initiated talks with Slovakia's GTS EuStream. The first actual backhaul was conducted by RWE in February 2013 from Poland and Hungary. It was followed by GDF Suez, E.ON Energy Sales, Trailstone, and Advance Trading, and in 2015 - by Royal Dutch Shell and Statoil. In Q1 2015, Ukraine was able to import 5.8 BCM.

This reverse flow is commercially countered by Gazprom's surprisingly lenient pricing terms of $248 / 000 m3,5 a price that would have seemed unthinkable in early 2014. While the prospects for actual competition on the gas market are brighter than ever, the European gas traders at the conference stressed that a number of conditions needed to be met for the market to become truly competitive:

- introduce a network code based on Entry/Exit nomination

- as part of the above,

- have clear balancing rules and a designation of the mechanism to remunerate the supplier of last resort

- allow for flexibility in nomination and renominations, year-, quarter-, month- and day-ahead, and if possible intraday

- allow for unused capacities (of which Ukraine has a lot) to be released

- empower the market regulator to enforce the network code, and arbitrate disputes

- ensure laws and regulations are stable in time

- introduce a standard gas trading contract, such as the EFET contract

- have a straightforward gas trading licensing procedure based on the trader's network code proficiency and capitalisation

- if the above has been achieved, have gas trading hub where market prices are discovered. It was stressed that hubs do not create liquidity, they reflect it.

Ukraine is still an important gas transit country for Europe's market. Of 409 BCM [6] consumed in Europe in 2014, 59.4 were transited via Ukraine (30% less than in

2013). For obvious reasons, this fact has crystalized the European Commission's attention, even if Ukraine's importance as a transit country has decreased under the combined effects of Gazprom's circumventing North Stream pipelines (yearly capacity: 55 BCM, utilised at about 50% in 2014), Gazprom's dispatching decision to maximise flows through Belarus, and Europe's own declining gas demand since 2010.[7]

Reforms in Ukraine's gas market will also affect the country's role as a transit country. They may not change transit volumes per se, but they will allow European gas traders to purchase gas at the Russian-Ukrainian border. Gazprom will obviously not welcome this possibility, but it has announced that it would not renew its gas transit agreement with Ukraine after it expires in 2019. Until the Turkish Stream pipeline and its Turkish-Greek interconnector are built, the Russian gas giant will need to sell at the Ukrainian border to supply markets of Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, and the Balkans. Whichever pipeline will be built first, Gazprom's Turkish Stream, or the competing trans-Turkish TANAP pipeline, Ukraine will lose some of its importance as a transit country to these countries. At the same time, the country may gain in importance as a key logistical hub of the Eastring project connecting the Visegrad Four, i.e. Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary.

[1] Conference co-organized by NaftoGaz, NGBI and Grant Thornton on 23/04/2015 in Kiev

[2] www.epravda.com.ua/rus/publications/2014/10/24/500610/

[3] The tariff structure is counterintuitive, with increasing prices volume prices for larger domestic consumers.

[4] Draft law №2250 adopted by Ukraine's parliament on 9th April 2015

[6] Eurogas press release 25/03/2015

[7] www.naturalgaseurope.com/gazprom-antitrust-case-review-breugel-23348

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter