Oil & Gas Companies: The Dividend Puzzle

Are investors running away?

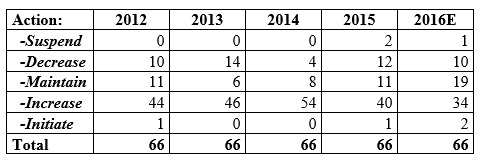

With a barrel of oil worth about $30 today and no clear signal of rebound, whereas for most companies the break even price is above $50, the harsh reality for the oil and gas industry is well expressed by the following: “The longer you’ve got low oil prices, the more companies will have to focus on pure survival” [1]. In this context the generous oil major’s payouts seem a bit quirky. A recent survey[2] provides indications on the dividend policy of large oil and gas companies (table 1)

Table 1

Dividend policy of large oil and gas firms (above $10 bn in market cap)

Source: Markit

For the year 2015 nearly 80% of companies have maintained or increased their dividend payments, and this proportion should remain the same in 2016 according to estimates. It is added: “pay-out ratios from Europe’s ten largest payers now stand at a massive 88%”. It seems astonishing while at the same time these companies are struggling to generate cash in a context where prices are depressed and should remain so for some time according to most experts. It appears all the more astonishing as one realises that investment expenses have to be reduced, operating assets sold and more debt taken to finance this generous dividend policy!

What might be the explanation? Deciding on dividends is a favoured topic for academics; therefore let’s consider the existing literature to address this question.

First one needs to stress the awkwardness of dividend cuts in the oil and gas industry. So far oil majors have been considered as low risk businesses generating a stable return, allowing for regular dividends. Hence before cutting dividends managers have to think twice. Let’s mention the emblematic case of Exxon Mobil, the company has increased its dividend year after year for over three decades. The case is not a singularity; other majors have adopted a similar approach. Taking this policy as an industry norm, so far well respected, unsurprisingly investors have sanctioned ENI, the Italian oil & gas leader, when it decided a 40% dividend cut for the year 2015 [3]. ENI’s share price fell by about 5% immediately after the announcement.

ENI’s case [4] is a good illustration of thesignalling theory, one of the most popular theories, and to a certain extent relevant, to reflect on dividend policy. When deciding on dividends managers send a signal to investors. Maintaining or even better increasing dividends suggest optimistic anticipations about future cash-flows. Investors ‘interpretation is that managers are confident in their ability to generate enough cash in the future so that there is no need for them to retain a high proportion of the net income. Inversely, when ENI decides to cut dividends and to abandon a share buy back program it clearly signals to investors a certain degree of pessimism, or at least perplexity, about the industry future. The consequence is an immediate negative impact on the share price.

In the present situation the problem is that ENI is probably right, the future of oil and gas companies very uncertain. Then how can one justify the positive attitude of others? Can one reasonably assume that most managers are confident enough to consider that oil and gas prices will definitely come back to a sustainable level soon? If that is not realistic, what else is driving their decision?

At this stage a reference to the agency theorycan be of some help. Information asymmetry is a concern for shareholders since well inform managers are likely to pursue their own objectives first rather than create value for them. A typical solution to handle this problem is to align objectives of both parties, and stock options were theoretically expected to achieve that [5]. However, with experience, it appeared that it was also necessary to maintain a certain pressure on managers to better control their action. The threat is particularly pregnant when the company is cash rich since in that case managers don’t need to rely on external funds to finance their plans. With cash at their disposal and inside information they are autonomous. Then imposing a high pay-out ratio and increasing the debt service is a way to limit the easy access to cash for managers, hence their autonomy.

Looking at past performance of oil and gas firms, shareholders may have good reasons to ask for their money in order to impose a cash constraint on managers. As noted in a 2015 report by Deloitte: « Returns of private global oil companies peaked a decade ago, well before crude hit record highs, indicating that they squandered the boom on vanity projects aimed at increasing production, with little thought for profitability [6]».The insufficient performance demonstrated by the industry when prices were high and cash easy, providing managers with a large degree of autonomy to allocate funds, could then be a justification for maintaining generous payouts. Demanding high dividends and in the mean time imposing a higher debt ratio can lead to a more rigorous allocation of now scarce funds. It makes sense, but is that argument solid enough to be convincing? Considering the present situation and prospects in the oil and gas industry, it is certainly not. A close look at the industry reveals that companies have to sell profitable assets, reject investment projects with positive Net Present Values (NPV) and even borrow more to pay dividends. If the objective of investors is only to regiment the behaviour of managers, under present circumstances that would be a bit too much. What is the justification for high dividends then?

What if investors had changed their mind about the future of the oil & gas industry, considering it has now entered its declining phase?

Even if the weight of fossil fuel is expected to decrease, there is no doubt that oil and gas will remain a dominant source of primary energy. However the climate change issue is gaining momentum and as the IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said « There should be no energy company in the world [which] believes that climate policies will not affect their business »[7]. Later, at the occasion of COP 21, Björn Otto Sverdrup, head of sustainability in Statoil, declared: « Changing the world’s energy mix is not easy. It will take time. Even with an exponential increase in investment in alternative energy, forecasts predict that fossil fuels will still make up a large share of the energy mix in 2040. Less than the 80% share of today, but almost certainly well over 50% »[8]. For sure, global economic growth will contribute to increase energy demand but may be not as much as expected if energy efficiency is significantly improved. In the end 50% of fossil fuel demand in 2040 may not be much higher than 80% of today’s demand [9].

In the mean time National Oil Companies (NOCs) are very active at preserving, or even increasing their market share, in the above already mentioned Deloitte report we can read: “NOCs do not seem to be cutting as steeply as IOCs. For instance, although IOCs are planning for a 13% drop in capital spending for the year, NOCs are cutting a considerably smaller percentage of their expenditures, while Saudi Aramco, ADNOC and Kuwait Oil Company may even increase spending. …In the realm of innovation, too, some NOCs are upping their game. ».

So the peak oil is no longer a menace, the present picture is weak demand growth with oversupply and competition from NOCs. Whether market prices will one day break even again remains an acute question for a number of players in the industry.

Furthermore, the progression of fossil fuel demand is not the only element to take into account. There are also other worrying factors at play. If environmental issues, in particular climate change, are now dealt with more seriously this will also affect the conditions under which the industry operates and raises funds. In particular the growing importance of Socially Responsible Investments (SRI) funds and green campaigns will change investor’s perception and attitude [10]. Financial performance could also be impacted would negative externalities be fairly priced. Adding to that the geopolitical tensions and the resulting increased difficulty to operate in some regions, all in all there is enough for investors to take their money and run away. Looking at the recent evolution of stock prices, some have already done so.

What if the situation deteriorates further increasing dramatically the perceived risk of financial distress for oil and gas firms? This scenario is very likely for a number of small highly leveraged companies engaged in the US shale venture, but may seem excessively pessimistic for majors. Nevertheless it is worth exploring that eventuality since it fits surprisingly well with facts.

The theory tells us that if a company is facing financial difficulties, with a substantial risk of defaulting, it may result in under investment. It comes from the fact that projects with positive NPV would benefit to creditors and not so much to shareholders because of limited liability.

Let’s imagine a company with 1 billion debt to be repaid in one year, and an estimated value of assets of 0.9 billion only at this date. Then, unless action is taken the company will default. Let’s further assume there is an opportunity to invest in a 0.2 billion project with expected future cash flow of 0.3 billion. The project has clearly a positive NPV and if accepted debt holders would definitely be better of with a good chance to get all their money back. But would it benefit to shareholders? The answer is no because it would just contribute to the full coverage of the debt with nothing left for them. Managers may then reject the investment opportunity since it would not create value for shareholders. This is a well-known case for underinvestment [11], which appears to be detrimental for creditors.

Going further, managers could even decide to sell valuable operating assets in order to generate cash to allow a generous dividend policy. This would be a way for shareholders to take money out of the company, at the detriment of creditors since the capacity to repay the debt would be reduced.

Effectively, oil majors invest less and even divest, they “sacrifice production to protect dividends” [12]. On one hand, due to underinvestment together with the sale of profitable operating assets, the cash flow generation capacity is reduced. On the other hand, large dividend payments resulting in lower proportion of equity in the balance sheet organises a risk transfer detrimental for creditors. A higher proportion of debt with a lower capacity to repay the debt, lenders feel concerned…they are right.

[1] Ian Reid, Macquarie analyst, cited by Ron Bousso in: “Oil sector’s lavish dividend policy in spot light as hard time grow”, Jan 29 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/europe-oil-dividends-idUSL8N15B3JE

[3] On Friday March 13, 2015, ENI cut its dividend from 1.12€ in 2014 to 0.8€ for the year 2015. A share buyback program was also suspended

[4] The high stake of the Italian state in ENI’s equity may explain the singularity of this case.

[5] See: Freek Vermeulen, « Why Stock Options Are a Bad Option », Harward Busines Review, April 21, 2009

[6]Oil and Gas Reality Check 2015, Deloitte

[7] Cited in the Economist: « Some oil majors are still ducking the issue of global warming », Nov 14th 2015

[8] Björn Otto Sverdrup, head of sustainability in Statoil, a Norwegian oil and gas company ; « My oil firm wants results from COP 21. But not the kind you might expect »; http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/27/cop-21-paris-climate-talks-low-carbon-oil-statoil

[9] Assuming a decrease in the weight of fossil fuels from 80% to 50% over the next 25 years, total energy demand needs to grow annually by 1.9% at least to maintain today’s absolute demand for fossil fuels in 2040. As world GDP growth is expected to come down significantly while a lot of efforts are made to increase energy efficiency, the stability of demand for fossil fuels for the years to come is far from unrealistic

[10] See : « Institutions worth $2.6 trillion have now pulled investments out of fossil fuels », The Guardian, 22/09/2015

[11] See: Myers, S. (1977), « Determinants of Corporate Borrowings »,Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 147-175

[12] Nick Cunningham, “Sacrifice-Production-To-Protect-Dividends”, September 2015, oilprice.com.

[13] Pay Dividends Or Keep Ratings, Dow Jones Business News, February 05, 2016

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter