Renewable and Nuclear Energy Integration to Support Responsible Growth in Developing Countries

Part 3: Energy Security

Last month, I posted the second of a few articles that will consider the responsible integration of renewable and nuclear generation to foster economic, social, and environmental improvements for developing countries in the mid to long term. The first article focused on economic expansion and the second article discussed possible socio-economic impacts. In this third article, the discussion will shift towards energy security, which continues to have major global ramifications as it has for hundreds of years.

The concept of energy security has different meanings to different groups and people. Bearing that in mind, it can be challenging to make meaningful comparisons and conclusions when circumstances can vary so widely from place-to-place and region-to-region. By using data from the World Energy Council, the goal will be to consider energy security from three key perspectives that can likely impact decision-making at the national and regional level.

World Energy Trilemma Index

Since 2010, the World Energy Council has prepared the World Energy Trilemma Index as a means to assess a country’s specific energy system performance in three specific dimensions:

- Energy Security – reflects the ability to meet current and projected future demand reliably. In addition, it also includes system robustness and the ability to swiftly respond to shocks with minimal disruptions. Domestic natural resources typically improve this number, as does diversifying the energy mix which also promotes system resilience.

- Energy Equity – assesses a country’s ability to provide universal access to affordable energy in a fair and equitable manner for personal and commercial use. Leading countries typically have high GDP, strong interconnections, and easily extractable domestic resources. However, this may slow supply diversification which could negatively affect the other two Index components.

- Environmental Sustainability – includes the energy system transition towards minimizing climate change impacts. Leaders tend to have national policies to diversify generation assets, strong energy efficiency measures, and a focus to extend the circumstances to all communities.

Naturally, individual circumstances such as natural resources, geographies, socio-economic systems, etc will dictate energy policies. And while there is no single solution that universally works or leads to a successful integrated energy plan, a thoughtful and well-informed process is far more likely to lead to a beneficial energy policy. For consideration purposes, the Trilemma Index can help us assess key thought processes.

American thinktank Third Way published a report in September 2020 considering which global countries may be capable of operating nuclear power plants by 2050. For consistency with the two previous articles, we will use the same groupings as detailed in Article 1.

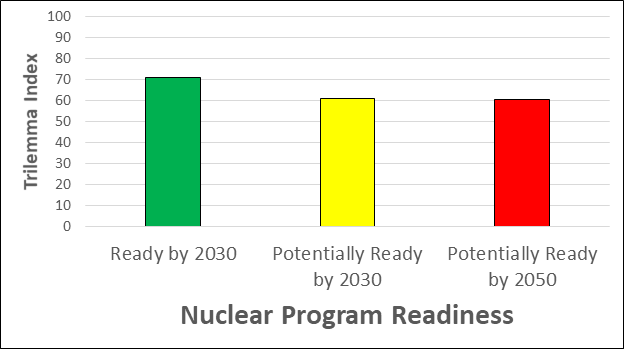

The aggregated Trilemma Index for the three groupings are shown below.

Figure 1: Trilemma Index by Grouping (Sources: Mapping the Global Market for Advanced Nuclear – Third Way, World_Energy_Trilemma_Index_2020_-_REPORT.pdf)

Figure 1 shows that both Potentially Ready groups have approximately the same Index and lag behind the Ready by 2030 group by roughly ten (10) Index points. But where is the divergence between the more advanced countries in green versus the countries in yellow and red? Figure 2 below breaks down the numbers further into the three (3) specific dimensions and from there, we can see where the separation is occurring.

Trilemma Energy Dimensions

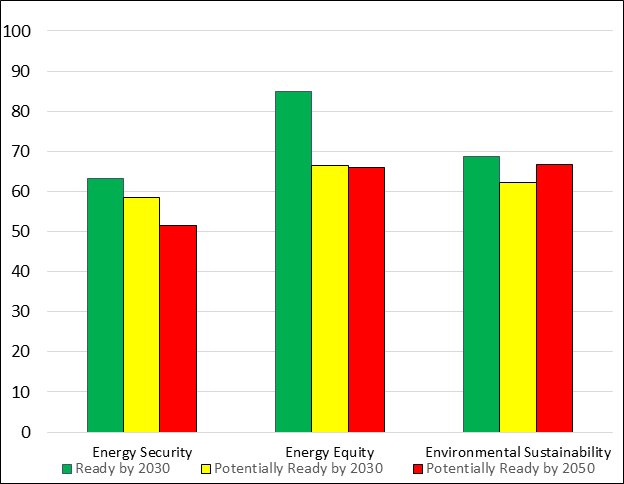

Figure 2: Trilemma Dimensions by Grouping (Sources: Mapping the Global Market for Advanced Nuclear – Third Way, World_Energy_Trilemma_Index_2020_-_REPORT.pdf)

Figure 2 shows the divergence is primarily in Energy Security and Energy Equity. Ready by 2030 countries have typically diversified their energy sectors to some extent already which helps increase their Energy Security score. They likely already have some mix of coal, gas, oil, nuclear, hydro, wind, solar, and others. The existing diversity (usually with some non-emitting portion) helps enhance their security by preventing an external source/country from having undue influence over domestic power generation. However, the search for coal and oil replacements provide certain challenges for Energy Security though, especially in Ready by 2030 countries – such as politically and with neighbours. One of the prime examples happening right now is the construction of the Nordstream 2 pipeline under the Baltic Sea to deliver gas from Russia to Germany. Simplistically, proponents of the pipeline support the need for alternate and diverse natural gas supply sources to western and central Europe while opponents caution against the possibility of increasing Russian influence in European Union countries.

The other notable difference between the three groupings is Energy Equity. Very clearly, the Potentially Ready in 2030 and 2050 groups lag ~15 points behind the Ready by 2030. Remembering that Energy Equity primarily relates to reliable and affordable energy supporting economic prosperity, it is obvious that the Potentially Ready countries need to increase their ability to make energy more widely available to the masses. Reviewing the countries in those groups, combined with the previous discussions in Article 1 and Article 2, we know that leading economic indicators lag in the Potentially Ready countries today but have larger growth rates in the future. By expanding the supply diversity and ability to supply more people, economic growth will naturally follow.

In the last dimension, environmental sustainability is quite level between the groupings –the Potentially Ready groupings have done well utilizing their indigenous non-emitting resources to date as has the Ready now group. The key for all will be finding the right way to responsibly expand their generation while not compromising environmental sustainability. In the Potentially Ready countries, this is especially true should they choose short-term fixes (such as natural gas) to meet projected economic growth. Short-term growth must not come at the expense of responsible growth, which likely will harm the environmental sustainability dimension.

Regional Dimension Differences

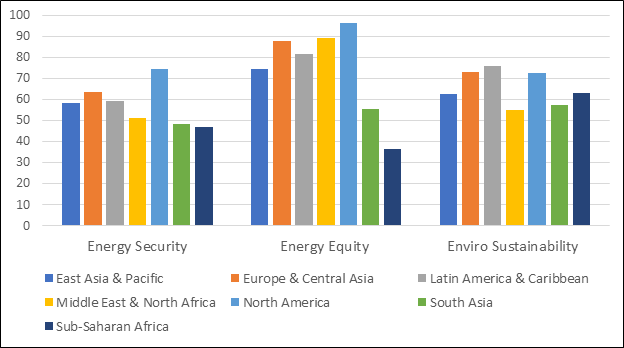

Figure 2 showed that Energy Security and Energy Equity diverged the most between the three categories, with Environmental Sustainability less so. But what about regional differences?

Figure 3 below with regional segmentation shows even more specifically where countries separate.

Figure 3: Trilemma Dimensions by Region (Sources: Mapping the Global Market for Advanced Nuclear – Third Way, World_Energy_Trilemma_Index_2020_-_REPORT.pdf)

Note that in Figure 3, the countries are not split into their Nuclear Readiness groupings. All the same countries are included in the data set but they instead are put into their corresponding regions. As a result, it becomes easier to pinpoint where the inequalities are most evident: 1) Energy Security for Middle East & North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, and 2) Energy Equity for South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Globally, almost one billion people still do not have access to basic energy, with a large portion of those concentrated in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. That accounts for the low Energy Equity scores for both regions and similarly low score for Energy Security. As seen in Articles 1 and 2, the responsible expansion of diverse power generation will positively impact economic growth as well as social improvements – while simultaneously improving Energy Security and Energy Equity. That is a virtuous cycle that all countries should push to achieve.

We also see a bit of variation in Environmental Sustainability with the Middle East & North Africa and South Asia regions. This occurs because both of those regions still use substantial amounts of carbon-emitting generation by virtue of their substantial natural resources (oil and gas). The Middle East & North Africa region has done a nice job with Energy Equity and making power available to a broad spectrum of their citizens, but the generation portfolio still tends to lack substantial diversity. That is likely to change in the future as many of those countries consider solar, wind, and nuclear options which would certainly help them with both the Energy Security and Energy Sustainability dimensions.

A country’s energy security can have huge impacts on their economy, social structure, and policy decision-making. It simply cannot be ignored and must be considered at every step to see how energy development can support a country’s national security and sovereignty while simultaneously improving citizens lives.

Conclusion

The three dimensions of the Energy Trilemma are inevitably linked, shifts with one will affect the other two in some way. Developed countries frequently built their economies on emitting generations and are now retroactively going back to adjust. However, countries in the two Potentially Ready categories may find themselves in a different situation – developing their economies using non-emitting generation which can potentially challenge Energy Security while they are simultaneously pushing to increase Energy Equity and improve Environmental Sustainability.

Many of the countries in the Potentially Ready categories still have generation deficits that will require additional plant development. Inevitably, and with a nod to diversification and improving the Energy Trilemma dimensions, the new generation will strongly favour some combination of non-emitting (wind, solar, hydro, nuclear) and reduced-emission generation (natural gas).

But perhaps a shift in thinking is necessary; perhaps countries and companies should consider generation plants more as heat sources that have tremendous potential to address very broad economic, social, security, and environmental concerns. Heat that can generate electricity OR hydrogen production OR energy/thermal storage OR district heating OR water desalination OR industrial heating applications OR….. Power plants no longer need to be limited to only generating power and the linear thinking of the past. For sure, a stable electric grid is a backbone of development and economic growth. But so many more options are available with emerging technologies that we no longer need to limit ourselves. And they can serve different masters, addressing multiple ideas above, sometimes simultaneously. Once our thinking expands, the trickle-down positive economic, social, and security benefits will blossom.

What’s Next?

Economic growth, social advancement, and energy security are three of the biggest considerations for countries evaluating their current and future energy structures. But what do some of the growth projections look like from international energy organizations? Who may be expanding and with what technologies? Next, we’ll look at some projections and see what they may offer in the crystal ball.

John Valentino is the International Clients Director at Centrus Energy and graduate of ESCP Business School’s Executive Master in Energy Management (Class of 2019).

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of ESCP Business School.

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter