Is Oil Supremacy on the Wane?

The amazing age of oil

When Edwin Drake drilled one of the world’s first commercial oil wells in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859, he definitely could not have anticipated the tremendous impact his drilling would have on the global economy, civilization and warfare in the years that followed.

Who gets what?

Source: Front cover of Dr Mamdouh G Salameh’s book“Over a Barrel" published in in June 2004

Since then, oil has been the lifeblood of the industrial world’s progress and standard of living. Innumerable everyday products – from pharmaceuticals to computers- depend on oil and its refining into complex chemicals and plastics. Modern industrial farming, which feeds much of the world, would grind to a halt if it were deprived of diesel-powered tractors, oil-and gas-based fertilizers to grow and harvest crops and the fossil fuels to process, package and ship food worldwide to feed a world population that has skyrocketed from 1.5 billion at the start of the oil age to 7 billion now.

Though the modern history of oil begins in the latter half of the 19th century, it is the 20th century that has been completely transformed by the advent of oil. The 20th century was truly the century of oil whilst the 21st century would be the century of peak oil and the resulting oil wars. No other commodity has been so intimately intertwined with national strategies and global politics and power as oil. The close connection between oil and conflict derives from three essential features of oil: (1) its vital importance to the economy and military power of nations; (2) its irregular geographic distribution; and (3) peak oil.

Conventional oil production peaked in 2006. As a result, any energy gap during the coming years will have to be filled with unconventional and renewable energy sources. However, it is very doubtful as to whether these resources could bridge the energy gap in time as to be able to create a sustainable future energy supply.

There is no doubt that oil is a leading cause of war. Oil fuels international conflict through four distinct mechanisms: (1) resource wars, in which states try to acquire oil reserves by force; (2) the externalization of civil wars in oil-producing nations (Libya as an example); (3) conflicts triggered by the prospect of oil-market domination such as the United States' war with Iraq over Kuwait in 1991; (4) clashes over control of oil transit routes such as shipping lanes and pipelines (closure of the Strait of Hormuz or the Strait of Malacca for example).

Between 1941 and 2014, at least ten wars have been fought over oil, prominent among them the 21st century’s first oil war, the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Oil was central to the course and outcome of World War II in both the Far East and Europe. One of the allied powers’ strategic advantages in World War II was that they controlled 86% of the world’s oil reserves. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour was about oil security. Among Hitler’s most cherished strategic objectives in the invasion of the former Soviet Union was the capture of the oilfields in the Caucasus. In the Cold War years, the battle for the control of oil resources between international oil companies and developing countries was a major incentive and inspiration behind the great drama of de-colonization and emergent nationalism.

During the 20th century, oil emerged as an effective instrument of power. The emergence of the United States as the world’s leading power during the 20th century coincided with the discovery of oil in America and the replacement of coal by oil as the main energy source. As the age of coal gave way to oil, Great Britain, the world’s first coal superpower, gave way to the United States, the world’s first oil superpower.

At present, there are at least five major conflicts that could potentially flare up over oil and gas resources in the next three decades of the twenty-first century. The most dangerous among them are a conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran over Iran’s nuclear programme and primacy in the Gulf region and a conflict between China and the United States that has the potential to escalate to war over dwindling oil resources or over Taiwan or over the disputed Islands in the South China Sea claimed by both China and Japan with the United States coming to the defence of Japan.

Yet oil has also proved that it can be a blessing for some and a curse for others. Since its discovery, it has bedevilled the Middle East and the world at large with conflicts and wars. Oil was at the very heart of the first post-Cold War crisis of the 1990s – the Gulf War. The Soviet Union squandered its enormous oil earnings in the 1970s and 1980s in a futile arms race with the United States. And the United States, once the largest oil producer and still its largest consumer, must import 41% of its oil needs, weakening its overall strategic position and adding greatly to its huge outstanding debts – a precarious position for the only superpower in the world.

As in the 20th century, oil will continue in the 21st century to fuel the global struggles for political and economic primacy. Much blood will continue to be spilled in its name as long as oil holds a central place in the global economy.

Oil’s firm grip on the global economy

Those who are already starting to talk prematurely about the decline of the supremacy of oil should think again. They should look no further than the adverse impact that the collapse of oil prices since July 2014 has had on the global economy.

The global economy has not been able to reconcile itself with the collapse of oil prices because the main ingredients that make up the global economy such as global investments, the oil industry and the economies of the oil-producing countries, are all being undermined.

While it is true that low oil prices could reduce the cost of manufacturing, thus helping the global economy to grow, it is a short-term benefit as this is vastly offset by a curtailment of global investment which forces companies around the world to cut spending, sell assets and make thousands, if not millions, of people redundant.

There has been a loss of 0.75%-1.00% annually in global economic growth since 2014.

The seven major oil companies in the world - Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Total, ENI and Statoil - need a price of $125-$135/barrel to balance their books. They also need certainty about the future trend of oil prices before committing themselves to huge investment in exploration and production.

As a result of declining oil prices, the oil majors have already sold many of their production assets and have cancelled more than $200 bn in oil & gas investments so far, which will translate in two years' time into a smaller share in the global oil production. Oil production by the major oil companies: Exxon Mobil, Shell, Total, Chevron and ENI has declined from 11.5 million barrels a day (mbd) in 2003 to 9.5 mbd in 2015. This will be reflected in steeper oil prices in the near future.

At prices much below $75 a barrel, some of the North Sea’s remaining economically-recoverable reserves, estimated at 15 and 16.5 billion barrels (bb) of oil and natural gas, will end up as so-called stranded assets - hydrocarbons that are simply too expensive to develop.

Moreover, global investment in upstream exploration from 2014 to 2020 will be $1.8 trillion less than previously assumed, according to leading US consultants IHS.

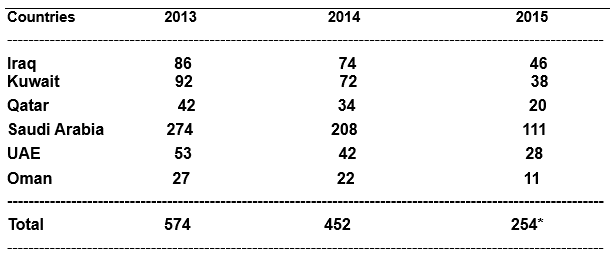

The Arab Gulf oil producers earned $574 bn in net oil export revenues in 2013. My calculations show that they earned an estimated $452 bn in 2014, down 21% on 2013 earnings. Their earnings in 2015 were estimated at $254 bn based on an average oil price of $40/barrel. The Arab Gulf oil producers have lost a total of $320 bn in oil revenues in 2014 & 2015 (see Table 1).

Table 1

Net Oil Export Revenues of the Arab Gulf Oil Producers

(US$ bn)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) 2014 Short-term Energy Outlook (STEO) / Author’s projections for earnings in 2014 &2015

As for the United States, it is doubtful whether the steep decline in oil prices would provide a boost to the US economic recovery. While the price decline would certainly provide the equivalent of a sizable tax cut for US consumers, it will deliver a major blow to the increasingly important US oil industry which is estimated to employ around 2% of the US workforce. It is also raising the risk of major defaults on the $200 billion in loans that have been extended to the domestic shale oil industry. The cost of servicing that debt has also increased exponentially after a number of operators saw their ratings reduced to junk.

For Russia, the combination of sanctions over the Ukraine crisis and falling oil prices has adversely affected the Russian economy by sending it to recession and causing the Russian currency to lose 40% of its value against the dollar. Russian GDP was reported to have shrunk by a projected 1.7% in 2015.

A continuation of low oil prices leaves no winners only losers. It also demonstrates the destructive power of low oil prices.

Are we on the verge of a post-oil era?

A few experts have been projecting the advent of the post-oil era within the next fifty years. The underlying assumption is that alternatives to oil would have been fully and cheaply developed by then thus ushering the post-oil era.

There is no doubt that global energy’s future is in renewables. Solar power along with other alternative energy sources will ultimately provide all the electricity we need, will power water desalination plants and will drive our transport.

And while renewable energy sources have made great strides in the last twenty five years, it will take their enabling technologies probably fifty years more before renewable energy sources start to have a decisive impact on electricity generation and transport. In 2015, renewable energy accounted for only 2.8% of the global primary energy consumption.

And although electric cars have already made their appearance on our roads, it will take many decades before they make an impact on the global demand for oil for transportation let alone replacing oil in the transport sector. Therefore talking about the advent of the post-oil era within the next fifty years is premature to say the least.

However, for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman - there would be no post-oil era ever.

Contrary to widely accepted wisdom, oil will remain an integral part of the Middle East economies throughout the 21st century and far beyond. Even if cheap alternatives to oil in transport, water desalination and electricity generation were to become readily available in the future, oil will not be left underground because the Arab Gulf oil producers will use it to power thousands of water desalination plants to generate enough water not only for drinking but also for irrigation to make the desert bloom again. They will also use it to dominate the global petrochemical industries and any industries in which oil is a feedstock.

Conclusions

Whilst renewable energy has made great strides in recent years in electricity generation, its impact on the transport sector is still negligible. It will take more than five decades before electric cars could start to make an impression on the global oil demand for transport.

And while experts around the world sit in their ivory towers and project the advent of the post-oil era within the next fifty years, the realities of the situation cast doubt on their projections.

So to the question as to whether Oil supremacy is on the wane, my answer is an emphatic No. Oil will continue to reign supreme through the 21st century and maybe beyond.

*Dr Mamdouh G. Salameh is an international oil economist. He is one of the world’s leading experts on the economics and geopolitics of oil and energy. He is also a visiting professor of energy economics at the ESCP Business School in London.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of ESCP Business School.

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter