Has the European Commission Softened on Gazprom?

The end of October was marked by two surprising moves by the European Commission toward the Russian gas giant, Gazprom.

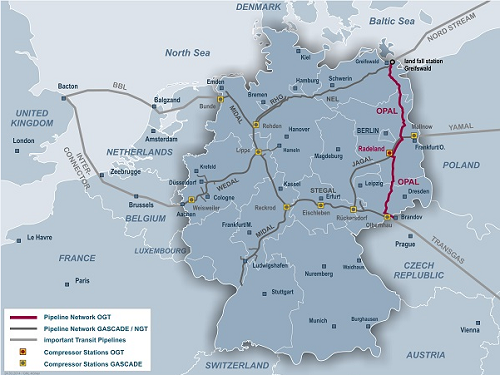

After years of confrontation Brussels decided to permit Gazprom to use almost 90% of the OPAL gas pipeline, located in Eastern Germany. Almost simultaneously there were information leaks about a deal between the two players on the competition case. Apparently, both sides found a way to settle the row in a satisfactory way.

Source: Gazprom

In 2011, the Commission’s antimonopoly branch, led by Commissioner Margrete Vestager, started a highly publicized investigation against Gazprom. On request of some Eastern European countries, Lithuania in the first place, Brussels decided to verify if some long term gas delivery contracts were breaking European competition rules. Russians claimed they were acting in conformity with the legislation and their contracts were based on the “market situation.” After years of hard bargaining, with almost no information about the actual discussions held behind the scene, the problem is now nearing a final settlement with an unexpected ‘win-win’ finale.

The OPAL story has an extensive background. The facility was planned and built as an on-shore prolongation of the off-shore Nord Stream on the Baltic Sea, stretching from Russia to Germany. Once built, the German and European regulators ruled out that Gazprom and its affiliates could use only half of OPAL’s throughput capacity: the other half should be reserved to third parties, as stipulated by the EU Third Energy Package. No third party was actually detected in this particular region, so the pipeline has been used at half of its capacity for many years. Now the situation will change.

The reaction of some EU countries, especially Poland and the Baltic States, was extremely critical of Brussels’s decision. Russia seems to be satisfied with the outcome. But there is still no clear indication of what has been the hidden motivation behind the Commission’s decision. The new state of play demands a ‘reasonable’ interpretation of the surprising events.

EIRA supposes that the two rulings on Gazprom cases reflect the possible end of the EU-Russia standoff on natural gas issues; maybe it would be the first step toward normalization of their turbulent relations.

The Commission might have reasoned the two cases against Gazprom in the following way.

- The XXI century will be the century of natural gas, even with the promotion of renewables in the energy mix. There is an on-going controversy over the exact figures, but not on the forecast itself: gas will remain a very important and relatively non-polluting energy source compared to other fossil fuels, with its growing applications in transport, including in bunkering. For the EU energy security it makes sense to secure preemptively secure sources for natural gas imports.

- European gas production is in decline, including North Sea fields. Shale gas production turned out to be economically unsustainable meaning too expensive (Poland is the showcase of it) or potentially too small to make a difference. Other sources of pipeline gas are either limited (Azerbaijan) or come from more and more insecure regions (Libya, Algeria), or are bound to other destinations than Europe (Iran). LNG deliveries of different origin, including LNG from Qatar and now also from the US, are on average more expensive than pipeline gas, but would form part of the energy balance in order to diversify sources. All attempts to get rid of Gazprom’s pipeline gas proved to be unsuccessful, because of absence of geologically and economically viable alternatives.

- Under the circumstances, Brussels has the obligation to secure certain volumes of imported gas of Russian origin without abandoning the search for new providers and continuing to promote the renewables.

This somewhat apolitical approach is shared by the European energy industry. If justified, then one may soon witness competition between various European regions and countries for contracting additional Russian gas supplies, which are huge but evidently not endless.

Up to now there are two main routes for Russian gas to Europe: through Ukraine (one line bound to Central Europe, the second line to the Balkans) and via Nord Stream to Germany. The Ukrainian route is in a very bad technical shape due to lack of proper maintenance during the last 25 years. There are controversies in the estimates of the badly needed investments for the renewal and refurbishment of the Ukrainian gas transportation network. However, no energy company has shown interest to either purchase a share of it or get involved in its upgrade when the Government in Kiev made such an offer. It looks like it will be used within certain limits, but in the foreseeable future the Ukrainian gas transportation infrastructure will lose its appeal for purely technical reasons.

From Gazprom’s point of view, the two new pipeline projects spearheaded by the company are cheaper and politically safer than the option of renovating the Ukrainian gas transportation network. These projects are Nord Stream-2 and Turkish Stream.

So far, Germany has been pushing for the implementation of Nord Stream-2, which would make it the major European gas hub. In that perspective most of the EU member states, including the countries of the South, will receive gas from Germany, and for the poorer Southerners this gas would be more expensive due to higher transportation costs. In Italy, there is a lot of opposition to Nord Stream-2. The logic is simple: Germany is the European leader in promoting sanctions against Russia but it wants to secure the cheapest Russian natural gas for Germany first and foremost!

Turkey also seems to have secured one line of the Turkish Stream, which will substitute deliveries now going through Ukraine to the Istanbul region and to the industrialized Western part of the country. The possible controversies could be sparked over the second line of the Turkish Stream designed to source other countries in Southern Europe. Where would it go? The options are clear: Greece and Southern Italy (that part of Italy is fed now by gas from Libya and Algeria) or Bulgaria and other Balkan countries? Russia declares that it will build the pipeline from Turkey to the EU only provided it has written guarantees from Brussels and is now waiting for the best proposal.

Anyway, if there is enhanced competition for Russian gas between different European regions, there will be more competition on the gas market as a whole. It will compel other producers to make better offers to the buyers. With less politics on the energy market, the winner will be the European consumer and the European economy.

Or is it wishful thinking?

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of ESCP Business School.

Useful links:

ESCP Business School

Executive Master in Energy Management

MSc in Energy Management

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter