Geopolitics & Oil in the Battle for Mosul

On June 10, 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) – surprised the world by advancing into several territories of central and northern Iraq. Most notably, ISIS has taken over Iraq’s second biggest city, Mosul. ISIS has also tried to gain control of the oil-rich area of Kirkuk (which is now under the control of Iraqi Kurdish forces). ISIS’ offensive has left Iraq in a dire situation, ridden by sectarian and ethnic conflict.

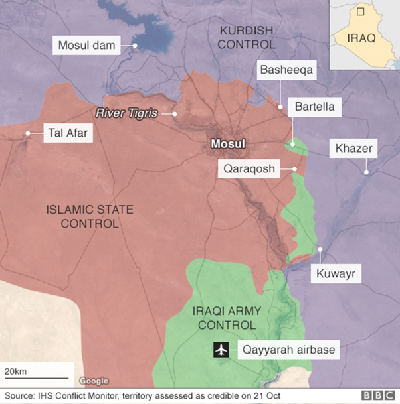

However, an overwhelmingly Iraqi force of 30,000 with a contribution from Iraqi Kurdish (Peshmerga) forces are now closing on Mosul with Western air support (see Map).

Source: BBC

Mosul will be liberated no matter how much it takes. However, there will be huge geopolitical implications for victory. These implications range from the impact on oil prices and Iraq’s northern oil resources including Kirkuk, potential independence of Iraqi Kurdistan, restoration of Iraqi territorial integrity and the inevitable defeat of ISIS in Syria.

Impact on Oil Prices & Iraqi Northern Oilfields

The liberation of Mosul will not lead to a rise in oil prices. If any, it might exert some small downward pressure on oil prices as it will enable both Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan to access more oil from Kirkuk oilfield and other much smaller fields still under control of ISIS. This means that in the fullness of time total Iraqi oil production and exports could rise to 5 million barrels a day (mbd) and 4 mbd respectively from the current 4.63 mbd and 3.69 mbd.

The Kurdish region is home to Iraq's major northern oilfields but a quarrel over who benefits from export revenues has become a prolonged, tangled and emotive dispute between the central government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

In early 2014 Baghdad slashed funds to the KRG, which then began exporting oil independently via a pipeline to the Turkish port of Ceyhan on the Mediterranean.

And in March 2016 Iraq's state-run North Oil Company (NOC) stopped pumping crude through the pipeline from fields it operates in Kirkuk. The move cut Kurdish oil revenues by around a quarter, worsening the budget crisis in Erbil amid low oil prices and the fight against the ISIS.

However, under a recent agreement, up to 150,000 barrels a day (b/d) of oil are being exported as a 50/50 split between the KRG and Baghdad.

Moreover, a reconciliation between the KRG and Iraq could attract more foreign investment to northern Iraq which is home to a third of overall Iraqi oil & gas reserves amounting to 47 billion barrels of oil (bb) and 43 trillion cubic feet (tcf) respectively.

The KRG has seized the opportunity to extend their territories to areas that have thus far been subject to contestation between themselves and the central government in Baghdad. After a battle with ISIS, they have taken over Kirkuk, a key-area for the energy security of Kurdistan, Iraq, and the wider region. In parallel, Kurds have started to strongly claim more autonomy, moving towards independence.

And to reaffirm its autonomy and also to enhance its oil exports, Iraqi Kurdistan has built a 25-mile oil pipeline from Dohuk inside the territory to Fishkabur in Turkey. The pipeline secures an export route for an initial 150,000 b/d (rising eventually to 300,000 b/d) and is significant because the crude goes via Turkey rather than using the Iraqi-Turkish Pipeline (ITP) from Kirkuk to Ceyhan on the Mediterranean.

The Kurdish region could potentially produce up to 1 mbd of oil by 2020, or 825,000 b/d more liquids than in 2011. Yet, like the rest of Iraq, it is constrained by the lack of infrastructure and export capacity. Moreover, without some kind of agreement with the central Iraqi government, many international oil companies have always been cautious about making major investments in the region. All this could technically cut the overall Kurdish production capacity by 2020 from the projected 825,000 b/d to 325,000 b/d by then.

Growing Calls for Iraqi Kurdistan’s Independence

Iraqi Kurds (the Peshmerga) are expected to play a crucial role in the battle of Mosul, which began on October 17 and is being led by Iraqi forces. They hope their reward will finally be independence—or at least greater sovereignty. Unfortunately for the Kurds, it’s not entirely up to them, and it never has been.

Since the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, the country’s Kurds have controlled a semiautonomous region in the north. Now, two years after the fall of Mosul to ISIS, Iraq’s Kurds hope to leverage a victory as well. If the coalition succeeds in Mosul, it could have significant consequences for them. Masoud Barzani, president of the Iraqi Kurdistan region, has been openly pushing for independence.

However, an independent Kurdistan would throw the region into greater turmoil. How viable is a landlocked state that is dependent on exporting natural resources through a corridor plagued by a violent conflict?

But oil isn’t a panacea for Iraqi Kurds; revenue is currently low due to the collapse in prices, and there are continued budget disputes with the Iraqi government. The result has been a loss in profit that, coupled with the cost of fighting ISIS, has drastically eroded Kurdish finances.

These obstacles will likely delay Kurdish independence. While there is no doubt that the Kurdistan region is heading towards self-determination, Kurdish independence, in the short term, is unrealistic.”

Other Geopolitical Implications

The liberation of Mosul will definitely impact on countries from Turkey and Saudi Arabia to Iran and Syria. A victory in Mosul will break the backbone of the ISIS and will eventually lead to their demise in Syria with the axis of Russia, Iran and Syria emerging victorious in the civil war which has been raging since 2011. By definition, this could be interpreted as a defeat for Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United States.

Moreover, a victory in Mosul could have a serious impact on the regional balance of power. It will further give rise to new alliances, as well as new patterns of enmity and amity. Turkey and Israel are already developing good relations with Iraqi Kurdistan; Iran and Iraq are maintaining even closer ties than before.

Still, Ankara worries that if Iraqi Kurdistan declares independence, Kurdish groups in Syria and Turkey would do the same, threatening Ankara’s territorial claims as well as oil transportation routes within the country.

The US government, however, has not officially supported Kurdish independence in Iraq. Part of this is due to fears of greater chaos in the region. The other part has to do with Turkey.

However, the most dangerous conflict that could erupt in the aftermath of a victory in Mosul is one between Iraqi Kurdistan and an emboldened and confident Iraq demanding the return of Kirkuk to the authority of the central government in Baghdad and refusing bluntly any calls for Kurdish independence. Such a conflict could involve Iran, Turkey and Saudi Arabia and, by proxy, the United States and Russia.

The Mosul Question

Turkey has sent 2,000 troops into Iraq, where they are watching the massive military operation aimed at recapturing Mosul from the extremists. Baghdad maintains Turkey has violated its sovereignty and has issued an arrest warrant for an ex-Mosul governor who allegedly "invited" in the troops.

These latest in a series of military moves reveal how the government of President Tayyip Erdogan is reasserting its historic territorial claims while also trying to crush the country's mortal enemies — Kurdish separatists.

Ankara has fought ethnic Kurdish militias within its borders for decades to prevent the birth of a new country, Kurdistan, carved out of Turkey itself. So it has watched carefully as Syrian Kurdish YPG fighters secure large swaths of land along the Syrian-Turkish border.

To Turkey's government, these Kurds are no different to the outlawed PKK militants who have carried out a series of deadly bombings within Turkey in the last year. The group is trying to force Turkey to accept the Kurdish right to an independent state, which has been denied them for a century.

Perhaps more terrifying for Turkey, Kurdish groups have established a state in all but name in northern Iraq. The problem as Turkey sees it is that the Kurds want the same for northern Syria. And then they want to link the two, which is anathema to Ankara.

Something else is motivating Turkey apart from the Kurds, and this goes back 100 years.

The Turks emerged humiliated from World War I, their once great Ottoman Empire shattered and shared out among the victorious French, who took control of Syria and Lebanon, and the British, who moved into Iraq and Palestine.

One issue and one city has remained contentious to this day. What was dubbed "The Mosul Question" in the 1920s plagued the League of Nations that was the precursor to the United Nations.

Turkey desperately wanted to keep control of a city it had controlled for centuries and considered vital to its image as a rising power. The Turks have always coveted the region's oil wealth.

In a nut shell, Iraq may not be out of crisis even with a victory in Mosul.

*Dr Mamdouh G. Salameh is an international oil economist. He is one of the world’s leading experts on oil. He is also a visiting professor of energy economics at the ESCP Business School in London.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of ESCP Business School.

Useful links:

ESCP Business School

MSc in Energy Management

Executive Master in Energy Management

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter