How Vulnerable are the World’s Key Oil Chokepoints

While everyone has been watching the Strait of Hormuz amid rising tension between the US and Iran, a chokepoint on the other side of the Arabian Peninsula is now at the centre of attention.

The recent attack by the Houthi rebels in Yemen on two Saudi oil tankers each carrying 1 million barrels of oil in the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb and Saudi Arabia’s suspension of oil shipments through the Strait have demonstrated how vulnerable the world’s key oil chokepoints are and how easy it is to disrupt global oil traffic.

Four key world chokepoints of oil, namely the Straits of Hormuz, Bab al-Mandeb and Malacca and also the Suez Canal account for two-thirds of global oil trade traffic. 44.25 million barrels of oil travel daily through these chokepoints.

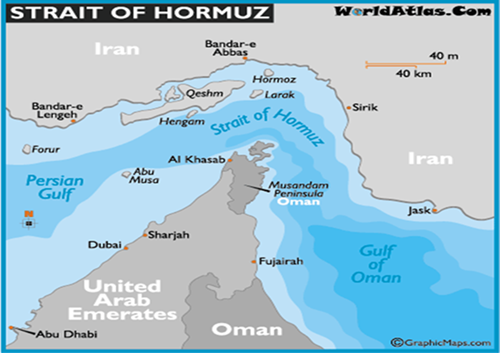

The Strait of Hormuz

Map 1

The Strait of Hormuz

Through this most vital chokepoint in the world, 17.75 million barrels a day (mbd) of and a third of global LNG supplies, pass every day. At its narrowest point, the Strait of Hormuz is only 21 miles wide.

Oil exports from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar (including large volumes of LNG exports), the UAE and Saudi Arabia must pass through the Strait. All of them with the exception of the UAE and to some extent Saudi Arabia will be seriously affected by any closure of the Strait of Hormuz.

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have pipelines that circumvent the Strait of Hormuz, but by and large these options are operating way below capacity.

Saudi Arabia has the 750-mile Petroline (or East-West Pipeline) which runs across Saudi Arabia from the oil fields in the East to the Red Sea in the West at the Yanbu port (see Map 2). It has a capacity of 4.8 mbd though its current throughput is 1.9 mbd which means that 2.9 mbd of the pipeline’s capacity sits idle.

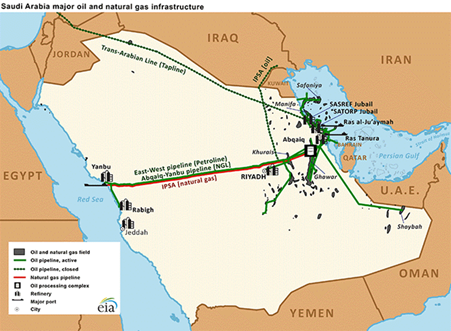

Map 2

The Saudi East-West (Petroline) Oil Pipeline

Through the Petroline, some Saudi oil can bypass both the Straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandb, linking up with tankers at Yanbu port in the Red Sea and from there towards the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean. Saudi Aramco has plans to boost capacity at the East-West pipeline to as much as 7 mbd but has so far made little progress on that front.

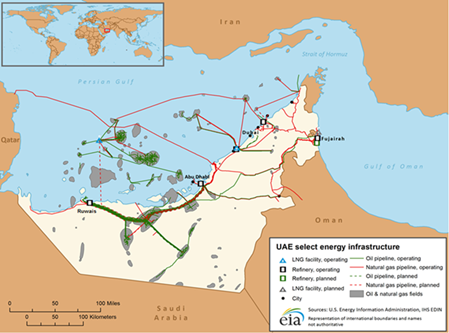

The UAE has the Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline, which has a capacity of 1.5 mbd. The pipeline runs from the Habshan onshore field in Abu Dhabi to Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman, bypassing Hormuz. About 500,000 barrels a day (b/d) of oil run through the pipeline currently with 1 mbd of unused capacity (see Map 3).

Map 3

UAE’s Habshan-Fujairah Oil Pipeline

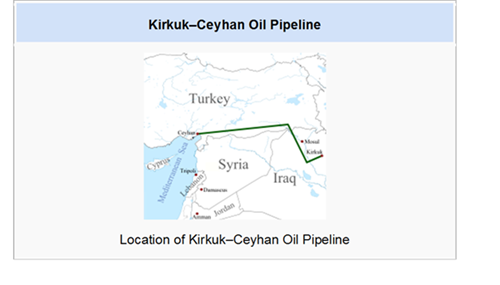

Iraq is now totally dependent on the Strait of Hormuz for its oil exports since the Iraqi-Turkish pipeline known as the ITP transporting Iraqi oil from Kirkuk to Ceyhan on the Turkish coast on the Mediterranean is currently out of action (see Map 4).

Map 4

The Iraqi-Turkish Oil Pipeline (ITP)

Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar have no alternative but to use the Strait of Hormuz.

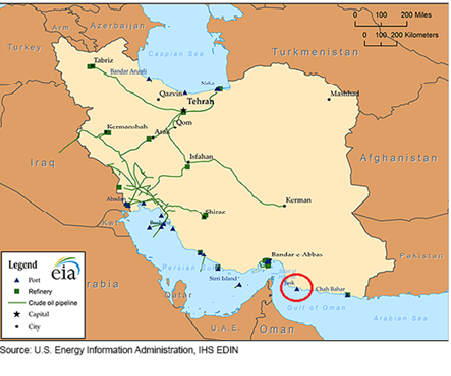

Meanwhile, Iran is building an oil export pipeline on its south eastern coast beyond the Strait of Hormuz expected to be operational by the early 2020s (see Map 5).

Map 5

Iran’s Proposed Oil Pipeline to Bypass the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Bab al-Mandeb

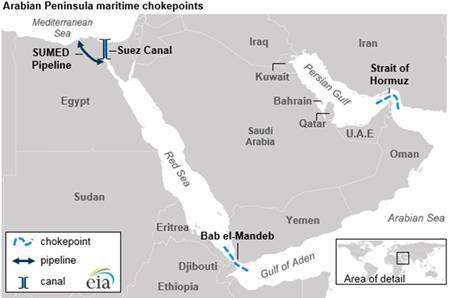

The Strait of Bab el-Mandeb is a narrow passage linking the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea with the Mediterranean (see Map 6).

Map 6

The Strait of Bab al-Mandeb

This chokepoint sees just under 5 mbd of oil traffic but its importance is magnified for two reasons. First, most oil that has to pass through the Suez Canal/SUMED pipeline must first pass through the Bab el-Mandeb so tankers have multiple obstacles on this Middle East-to-Europe route. Second, it is, at this point, close in proximity to the war in Yemen.

There are no alternatives to the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, except for the aforementioned Saudi petroline. A closure of the Strait would force tankers to travel around Africa’s southern coast.

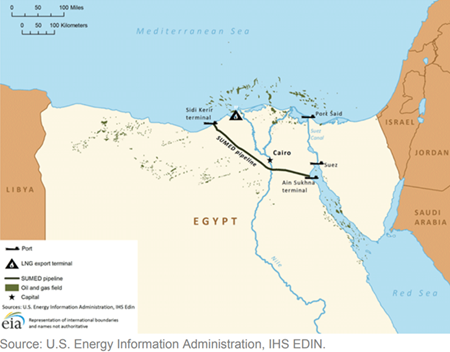

The Suez Canal & the SUMED Oil Pipeline

Located in Egypt, the Suez Canal is a third major chokepoint although the upside of this one is that it is located in a single country, not between multiple countries, such as the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca.

Combined with the SUMED pipeline, which bypasses the canal and connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, the two routes account for 8% of the world’s daily seaborne oil, or 5.5 mbd. Most of the oil goes north, from the Middle East to Europe (see Map 7).

Map 7

The Suez Canal & the SUMED Oil Pipeline

The Suez Canal cannot handle the largest oil ships, ultra-large crude carriers (ULCCs). It can only handle VLCCs that are not fully laden. As such, VLCCs can offload some of their cargo onto the SUMED pipeline, and then the lighter ship can pass through the canal, picking up the oil at the other end of the pipeline in the Mediterranean.

The SUMED pipeline can carry 2.34 mbd, and offers a hedge of sorts against an outage at the Suez Canal. It is the only alternative route that can bypass the Suez canal otherwise tankers would have to travel around the southern tip of Africa, adding 2,700 miles to the trip for a tanker traveling from Saudi Arabia to the United States.

The Strait of Malacca

The second most important chokepoint in terms of oil volumes is the Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Malaysia. More than 16 mbd pass through it.

The Strait is only 1.7 miles wide at its narrowest point, creating a natural bottleneck with the potential for collisions, grounding, or oil spills. China, the largest oil importer in the world, has a strategic interest in seeing uninterrupted tanker traffic through the Strait.

China is overwhelmingly dependent on the Strait as 80% of its oil imports pass through it and this vulnerability has led to several Chinese initiatives to find alternatives. The Strait links the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and is the main route for oil from the Middle East to reach Asian markets (see Map 8).

Map 8

The Strait of Malacca

China’s growing dependence on oil imports has created an increasing sense of ‘energy insecurity’ among Chinese leaders. Some Chinese analysts even refer to the possibility that the US is practicing an ‘energy containment’ policy toward China, or could implement one in the future.

With the American Navy patrolling the southern end of the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Navy patrolling the northern end, China feels sandwiched in and strategically vulnerable. The former president of China, Hu Jintao, has referred a number of times to what he describes as the ‘Malacca dilemma’.

China’s answer to the “Malacca Dilemma” was the newly-opened China-Myanmar crude oil pipeline (see Map 9).

Map 9

The China-Myanmar Crude Oil Pipeline

Iraqi crude oil for instance could be shipped from Ceyhan on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast and from there through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean instead of through the risk-prone Straits of Hormuz and Malacca before reaching Myanmar and entering China.

China financed the pipeline as part of its “One Belt, One Road” program, a massive infrastructure campaign across much of Asia.

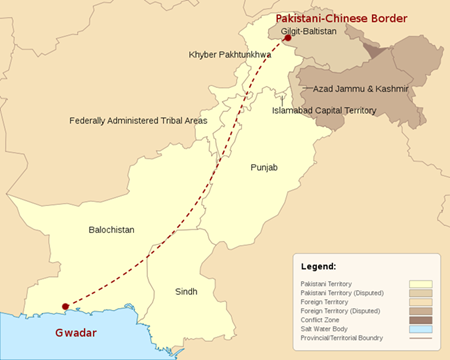

China has also been considering a multi-billion-dollar pipeline that would carry crude oil from Pakistan’s coastal port of Gwadar to Western China (see Map 10). That initiative has not broken ground, although Gwadar figures into a much broader strategic plan for China, beyond oil shipments.

Map 10

The Proposed Gwadar-Western China Oil Pipeline

Could These Chokepoints be Bypassed?

By and large, the alternative routes to these major chokepoints are only partial solutions, if at all. The oil trade is still highly dependent on these key chokepoints, and thus, highly vulnerable to any lengthy outage.

An outage at any of these locations, even for a brief period of time, has the potential to force steep oil price increases with the effects magnified by the size and duration of the outage. Even the whiff of a potential outage, particularly when the oil market is tight, can add a few dollars per barrel as a risk premium.

Still, a closure of any of the four chokepoints for a lengthy period of time could send oil prices far above $150 a barrel.

Iran has threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz if it was prevented from exporting its crude oil as a result of US sanctions. Iran’s threat should be taken seriously.

The Strait at its narrowest point is 21 mile wide so it is impossible militarily to close it completely. What Iran can do is mining it stealthily with the expectation of a mine hitting an oil tanker and sinking it. Such an accident in itself would deter tankers from crossing the Strait thus causing a disruption in oil supplies until the mines are cleared.

Alternatively, Iran could threaten sinking tankers crossing the Strait even if escorted by the US Fifth Navy in the Gulf. This threat might deter tanker owners around the world from sending their tankers across the Strait under pressure from global insurance companies until tension has subsided. In this way, Iran would have achieved its goal of disrupting oil supplies peacefully.

The Strait of Malacca at its narrowest point poses a natural bottleneck which could be blocked by a collision of two ships or even the sinking of one.

Because of its small width, the Suez canal is the easiest to block by a sinking of even a small vessel.

*Dr Mamdouh G. Salameh is an international oil economist. He is one of the world’s leading experts on oil. He is also a visiting professor of energy economics at the ESCP Business School in London.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of ESCP Business School.

Interested in becoming an energy expert and make a real impact in the industry? Check out how ESCP's programmes will equip you with the tools you'll need!

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter