BP's faustian bargain with Russia

In the wake of the downing of Malaysia Airline flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine on 17 of July 2014, Russia has been pelleted with adverse court rulings and judicial decisions. In sequence we have:

- 28/7/2014 : the Hague arbitration court's finding is that Russia did in fact steal Yukos from its rightful owners, the shareholders of the company, and must pay $50 billion damages as a result [1]

- 31/7/2014 : Europe's top human rights court awarded shareholders in Yukos 1.9 billion € in damages [2]

- 31/7/2014 : the European Council announced sectorial sanctions against the banking/financial, the weapons trade, and the oil sector.[3] In the latter, new investments, covering new investments after 1 / 8 / 2014

Of lesser economic importance but still in the spirit of the day, we also have the following cases :

- the investigation into the assassination of the Russian intelligence services transfuge Litvinentko in 2006 initiated only on 22/7/2014

- the mutual legal actions filed at the international arbitration court in Stockholm by Ukraine's Naftogaz Ukrainy and Russia's Gazprom against one another over the price of natural gas imports into Ukraine. The basis for this future ruling is the framework agreement for these imports dates back to 2009, when Russian-Ukrainian relations were far more cordial.

The sanctions will need some time to take effect. They affect new technology transfers or export of listed items for use in deep water oil exploration and production, Arctic oil exploration and production, and shale oil projects. This means it does not affect existing projects, and tellingly it does not apply to natural gas - why would Europe want to affect its own gas supplies ? The problem lies in the definition and interpretation of these restrictions:

- exploration and production technologies are largely the same for oil and for gas;

- fracking used for extracting shale oil and gas, has long been used for assisting the extraction of conventional oil and gas;

- finally, the restrictions do not define "deepwater" offshore. Indeed, yesterday's "deepwater" technology is today's ordinary offshore technology;

- even the distinction between the two is not always clear, as condensate is an intermediate product that can be classified as either.

The IOCs will doubtless require some guidance from their countries' agencies on how to understand these sanctions. There is no doubt that, if applied, these sanctions will hinder Russian companies ability to develop new deposits. No Russian company has ever acted as the developer and operator of offshore deposits. Regarding shale hydrocarbons, the picture for gas and oil is contrasted. Until 2012, shale gas was derided as being expensive and environmentally damaging. Today, it is not a priority in Russia as it possess significant conventional reserves. Shale oil holds promise in Western Siberia where the Bazhenov is thought to be the world's largest.[4]

International Oil Companies do not have it easy these days. In the face of assertive National Oil Companies globally, they are faced with fewer investment opportunities. In Russia, they are specifically invited to develop technically challenging reserves. On the offshore, foreign investors can only enter into JVs with Russian state-owned partners (i.e. Rosneft or Gazprom), and their share should be below 50%.

Every host country has its unique challenges for international oil companies, be it graft, political instability, insurgency or war, local content requirements, or mercurial petroleum laws. However, many of the complications encountered by foreign oil companies are Russia-specific. Under Russian subsoil law the information with respect to oil and gas reserves and their production in the Russian Federation as a whole, in any particular Russian region, or in "Federally significant deposit" is treated as a state secret.[5] Fortunately, this does not prevent publicly quoted Russian companies from having their reserves independently appraised. A 2008 amendment of this law states that the government can block the ownership of such federal deposits by foreign companies or foreign-controlled Russian companies. Finally, the license holders for such deposits must in effect be state-controlled oil and gas companies.

Also, until recently, Gazprom had a monopoly on lucrative natural gas exports. Since December 2013 Rosneft and Novatek, an independent Russian gas producer, can also export natural gas as LNG. However, both are targeted by sanctions, despite being BP and Total, respectively, as nearly 20% shareholders. Gazprom in the past bore the brunt of Russo-Ukrainian gas spats. This time, ironically, it may stand to benefit from its domestic competitors' misfortunates as it is not directly targeted by sanctions and it remains in charge of Russia's export pipelines.

Selected International Oil Company joint ventures in Russia

|

IOC |

Russian partner |

project, year entered |

nature of joint ventures |

|

BP |

Rosneft |

2013 |

various agreements to develop the Arctic offshore (West and East Siberian shelf, N and S Kara Sea, Russian Barent Sea) for a total BP net acreage of 140 000 km2. |

|

BP |

Rosneft |

May 2014 |

Agreement to explore the central Orenburg (lower Urals) region Domanic shale formation for oil. Equity: BP 49%, Rosneft 51% |

|

ExxonMobil XOM |

Rosneft |

December 2013 |

Shale or tight oil exploration potential in the Bazhenov and Achemov formations in Western Siberia (1 yr project) but also in Canada and Texas. |

|

ExxonMobil |

Rosneft |

1995 |

Sakhalin 1 project Equity: Exxon 30%, Rosneft 20%, Japan's SODECO 30%, India's ONGC Videsh 20%. |

|

ExxonMobil |

Rosneft |

2011 strategic agreement 2013 implementation |

ExxonMobil is working with Rosneft on the exploration potential in the Arctic seas (600 000 gross km2 JVs in the Kara and Black seas. Equity: Exxon 33%, Rosneft 67% |

|

ExxonMobil |

Rosneft |

2013

|

Rosneft had an option to purchase 25% in Exxon's Alaskan Point Thomson natural gas field. Rosneft retracted on 22 / 7 / 2014. |

|

ExxonMobil |

Ukrainian government |

2012 (suspended in February 2013) |

In August 2012, an ExxonMobil-led consortium won the tender for the Skifska offshore block in the Black Sea for 1.65 million net acres (ExxonMobil interest - 40 %). The block is now part of Russian-controlled Crimea. |

|

RD Shell RDS |

Gazprom |

1994 and 2000 |

Sakhalin 2 $22 billion natural gas development on the Russian Pacific. The project also includes a 9.6 million tons-per-annum liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals. Equities, initially: Shell 55%, Mitsui 25%, Mitsubishi 20%. Equities after "renegotiation" in April 2007: Gazprom 50%+1 shr, Shell 27.5%, Mitsui 12.5%, Mitsubishi 10% |

|

Total TOT |

Novatek |

December 2013 |

Final investment decision reached for Yamal LNG (16.5 mT/yr liquefaction capacity). The first production is expected late 2017. Equity: Total 20%, Novatek 60%, CNPC 20% |

|

Total |

Lukoil |

May 2014 |

Bazhenov shale gas development |

|

ENI |

Rosneft |

2013 |

Seismic exporation in the Russian Barents Sea and the Black Sea |

|

ENI |

GazpromNeft + Novatek |

2013 |

Divestment of ENI's stake in GazpromNeft and Novatek JV Yamal Development to its Russian for $2.9 bln |

|

Statoil |

Rosneft |

December 2013 |

JV to assess the feasibility of commercial production from the Domanik shale formation |

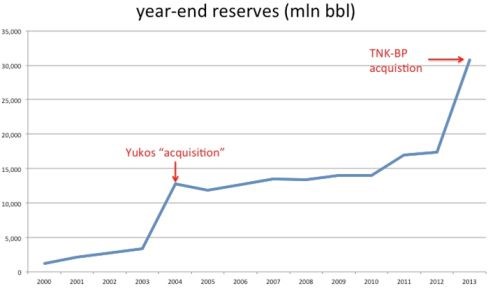

All the oil majors have some projects in Russia in one way or another in the upstream and on LNG liquefaction terminals. However, BP is in a class of its own in terms of exposure to Russia in general, to Rosneft in particular, and hence to its indirect exposure to the Yukos case. While the IOCs can be forgiven for not having predicted Russia's annexation of Crimea, they cannot claim they were unaware of the risks of doing business with a Rosneft. The company's oil-equivalent reserves grew by a factor of 3.8 to 12.7 bln bbl thanks to the "acquisition" in 2004 of Yukos' assets.[6] By comparison, BP's 2013 oil-equivalent reserves stood at 9.8 bln bbl.[7]

Rosneft's reserves (barrels of oil-equivalent)

In Russia, Gazprom is mainly responsible for gas fields, and Rosneft for oil fields. Because of its oil focus, Rosneft will be more affected by the sanctions. Furthermore, the US introduced sanctions preventing Rosneft, independent gas producer Novatek and named banks from raising long-term financing on capital markets.

Russia's oil sector would probably have no trouble sidestepping the financial leg of the sanctions with the help of Chinese capital. However China's oil companies will not be able to assist with the technological leg. For one, China's offshore petroleum technology lags behind the Western oil companies in deepwater offshore technology. Secondly, according to the Russian legislation (Subsoil Law 1992), only state-owned (more than 50% of the shares are owned by the state) oil and gas companies are allowed to participate in the development of offshore fields. This is inconsistent with Chinese firms' practices to take majority stakes and operational control of the projects they finance. The technology transfer ban, if it is properly enforced by the member states, will have a biting effect on Russia's plans to develop its Far East and Artic blocs. No Russian company has ever developed offshore oil or gas fields on its own, let alone ones in the Arctic sea, where drifting icebergs constitute a particular challenge.

This is quite an evolution from the initial round of sanctions against Russian individuals, which their targets derided as toothless.

BP's case is an especially good example of the perils for Western interests from the new sanctions. On 29 July 2014, the day sanctions were announced, BP published Q2 2014 profits 34% higher than for the same period in 2013, yet its stock fell 3.3%. It is one inconvenience for some oil companies not to be able to add to their existing investments in Russia or to transfer technology to them. It is another matter altogether if Yukos' lawyers can go after the company that accounts for 30% of its oil-equivalent hydrocarbon production, and 47% of its gross replacement cost profit.[8] Rosneft's shares fell 17% over July 2014.

After Deepwater Horizon, BP sold assets to pay its liabilities to become a "simpler company"[9]. If "simpler" means more focused on one country, it certainly achieved its aim. In March 2013, it entered into its landmark agreement by selling its 50% share in TNK-BP to Rosneft in exchange for nearly 20% of the Russian state oil company. The two companies' stated aim was to jointly explore and develop Russia's wide Arctic offshore. Robert Dudley, BP's CEO certainly knows something about the risks of doing business in and with Russia. When he headed BP Russia's operations in 2008 he had to go underground following intimidation from his business partners in TNK-BP. After he left Russia for his safety, he was in effect locked out of the country by visa restrictions. More than his oil industry peers, the writing about doing business in Russia was on the wall back then, but Mr. Dudley must have hoped his personal relationship with Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin would insulate BP. Now that this close Putin associate is personally targeted for sanctions, this association is more of a liability, and the "business as usual" stance of BP and other oil industry executives looks increasingly untenable.[10]

[1] http://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2014/07/28/hague-court-russia-did-steal-yukos-and-must-pay-50-billion-damages/

[3] Regulation 833/2014 and Council Decision 2014/512/CFSP

[4] http://www.unconventionaloilrussia.com/en/blog/bazhenov-formation-search-big-shale-oil-upper-salym/

[5] These reserves are defined as having more than 70 mln tons of oil or 50 bln m3 of gas, middling deposits by international standards. in the Law of Russia No. 2395-1 on Subsoil dated 21 February 1992 amended last in December 2011.

[6] Rosneft's Long Term debt also grew from $1.8 bln to $9 bln, implicitly pricing the barrel in the ground at under $1.

[7] Developed plus undeveloped reserves of BP subsidiaries, plus BP equity in other entities,

[8] Replacement cost profit is an accounting practice for reporting profits in the oil industry.

In the oil industry, the cost of goods sold varies significantly due to fluctuations in the price of oil. Replacement cost profit addresses this problem by letting oil companies base their cost of goods sold on the current price of oil, rather than the price at the time individual reserves were acquired.

Facebook

Facebook Linkedin

Linkedin Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube EMC Newsletter

EMC Newsletter